Typology analysis of fiscal Instruments for carbon abatement

Understanding Carbon Tax

The race to net zero demands efforts from all sectors and levels of governance. Fiscal instruments and taxation tools are often deployed by international, national and local governments to address the policy needs to carbon reduction. Despite the fact that there are some existing databases that survey the instruments regularly at a global scale, there is a lack of systematic analysis and theoretical understanding of the evolving instruments and their policy impacts on the net zero processes, as well as how countries learn from each other.

Given our climate research and practices carried out in Musecology, we propose the following approaches to collate and assess international evidence on the potential role of fiscal levers to deliver reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Needs for further research

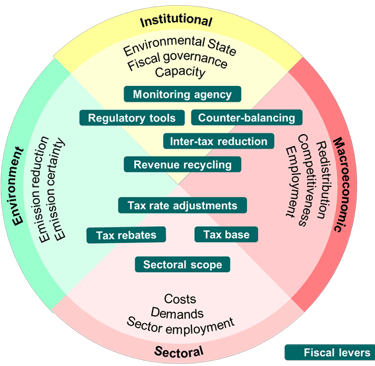

Focusing on environmental and macroeconomic impacts, existing studies on carbon tax (e.g. Alton et al, 2014; Andersson. 2019; Lee et al, 2012; Pereira et al, 2016; Yoshino et al, 2021) have neglected the institutional impacts on state capacity and fiscal governance. Adding a new layer of perspective to the ‘triple dividends’ considerations (Pereira et al, 2016; Maxim, 2020), this study proposes to examine outcomes of fiscal levers in GHG reduction in four dimensions: environment, macroeconomic, sectoral and institutional (see analytical diagram in Figure 2).

Successful implementation of any fiscal levers is conditioned by the capacity of environmental state. Environmental state is “a significant set of institutions and practices dedicated to the management of the environment and societal-environmental interactions”, which highlights “the agency of the state, as well as historically defined patterns of state institutionalisation that structure political interaction” (Duit et al, 2016; Mol & Buttel, 2002). Studies argued that the UK Treasury placed small priority on curbing carbon emissions in the conduct of fiscal policy (Craig, 2018). After the introduction of UK Net Zero Strategy in 2021, the policy environment and hence the environmental state have substantially altered. It is apt for a more comprehensive global case review structured by a valid analytical framework.

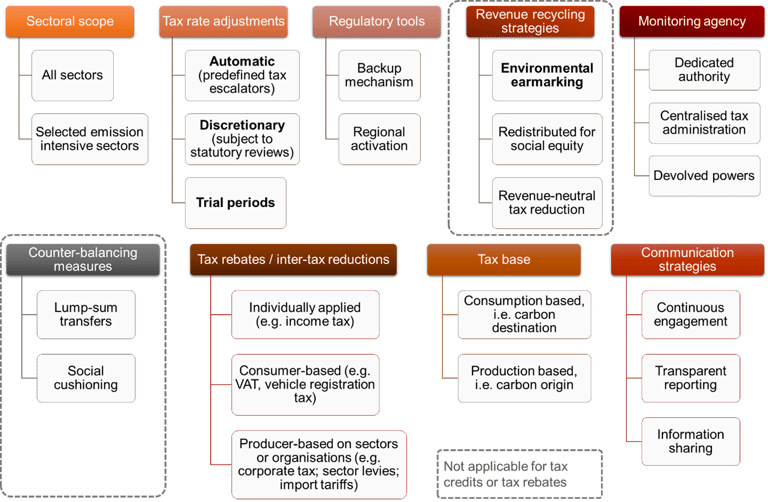

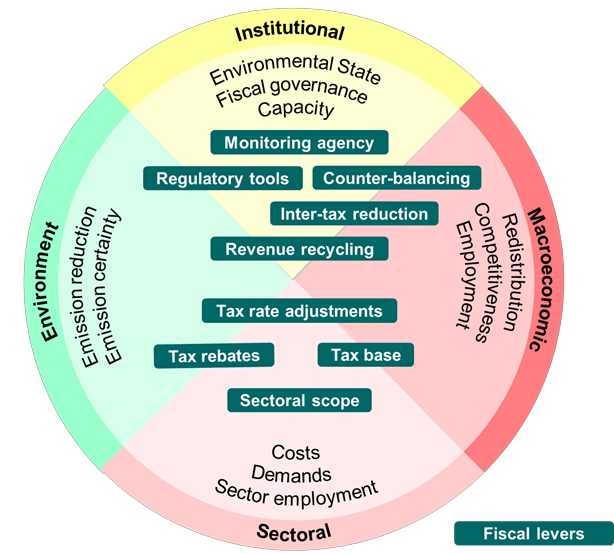

Figure 1. Typology building framework

Typology building

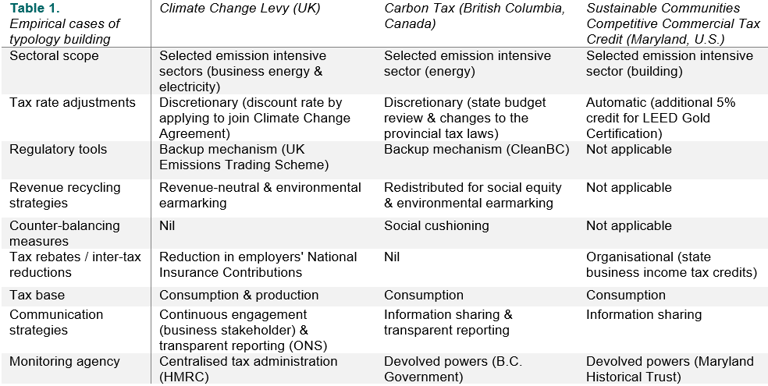

Identifying typology is the first step to generate analytical insights for comprehensive case review. To construct the typology, initial literature review has been conducted (further finetuning required). Figure 1 illustrates the typology building framework, demonstrated with selected empirical cases in Table 1.

The first differentiating component is about tax adjustments, i.e. the way tax rates are adjusted to reflect updated information about GHG emissions performance. Required tax level should be determined by the environmental objective and more specifically by the marginal costs of meeting a given emissions target (Carattini et al, 2018). The adjustment can be automatic with a pre-defined tax schedules or escalators, or discretionary triggered by dedicated statutory approval procedures (Murray et al, 2017), and a trial period can be included (Carattini et al, 2018). Increased tax rates can be applied to selected carbon intensive sectors. Tax adjustments thus lead to environmental and sectoral impacts.

If tax adjustments are inadequate for reaching cross-sector carbon reduction targets, regulatory tools such as regional emission trading mechanism or any environmental regulatory framework can function as a backup mechanism to promote emissions certainty, which can be activated within limited regions of a country with devolved tax administration authority (Murray et al, 2017). Coordination with regulatory tools generate institutional impacts on the environmental state.

Revenue recycling strategies are another key features of any Pigovian tax policies. The additional revenues can be environmentally earmarked to fund other emission reduction projects, redistributed to achieve a fairer (less fiscally regressive) outcome, or spent on reduction of other taxes to achieve a revenue-neutral outcome (Carattini et al, 2018; Murray et al, 2017). To redistribute the revenues, counter-balancing measures can be devised to mitigate disproportionate negative impact on low-income or remote households with either lump-sum transfers or social cushioning (Carattini et al, 2018). For the revenue-neutral outcome, it is feasible to couple carbon tax with other taxes imposed on individuals, organisations, consumers or producers, such as VAT (Andersson, 2019) or income tax (Lee et al, 2012). Given the various revenue recycling strategies, different fiscal policy designs can create environmental, institutional and/ or macroeconomic impacts.

For the choice of tax base, goods can be taxed for its consumption (carbon-destination basis) or production (carbon-origin basis) (Clarke 2011). There can be sectoral impacts with the choice of tax base.

To regulate the implementation of an introduced taxation, there should be a monitoring agency specified and delegated with rule-based coordination remit (Hallett & Hougaard Jensen, 2012). This agency can be a statutory organisation or its department with dedicated authority to administer environmental tax and/ or levies in relation to carbon reductions. The coordination of environmental tax can also be placed under the national centralised tax administration. For instance, it is the Australian Taxation Office that administers the Carbon Sink Forest Tax, instead of the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Furthermore, some devolved administrations or subnational governments can possess devolved fiscal powers to devise and collect environmental taxes or charges, such as the Carbon Tax implemented in British Columbia (B.C.) of Canada. The arrangements of monitoring agency impose institutional impacts.

Effectiveness assessment

Outcomes of the identified fiscal policies can be assessed in environmental, macroeconomic, sectoral and institutional dimensions (Figure 2). The environmental outcomes relate to carbon reduction effects, emissions certainty, and reduction of non-CO2 GHG (Lee et al, 2012; Mortha et al, 2021; Murray et al, 2017; Pereira et al, 2016).

Macroeconomic impacts are concerned with distributional effects, welfare consequences, costs of agents, potential competitiveness and employment effects (Carattini et al, 2018; Lee et al, 2012; Pereira et al, 2016; Yoshino et al, 2021). Impacts can vary by sectors, regarding increased operating costs of an industry, loss in demands in international trading of taxed goods, and sectoral employment (Lee et al, 2012).

Institutional outcomes are in relation with fiscal governance, fiscal capacity and ultimately reconfiguration of the environmental state. Good fiscal governance supports long-term structural reforms (Giosi et al, 2014), i.e. decarbonisation in this case. Studies in some countries have assessed how carbon tax may affect public finance integrity, budgetary position, public indebtedness, as well as the level of trust in tax policy and the government (Pereira et al, 2016; Carattini et al, 2018). Fiscal capacity should be assessed, which is about the potential ability of a local government to raise revenues from its own sources relative to the cost of its service responsibilities, with appropriate allowance for revenues received from central or other local governments. Three types of states in fiscal capacity are identified as common interest state, redistributive state and weak state (Besley et al, 2013). The common interest and redistributive states of fiscal capacity can reinforce the environmental state in different aspects as identified by Duit et al (2016).

Figure 2. Effective Assessment Outcome Diagram

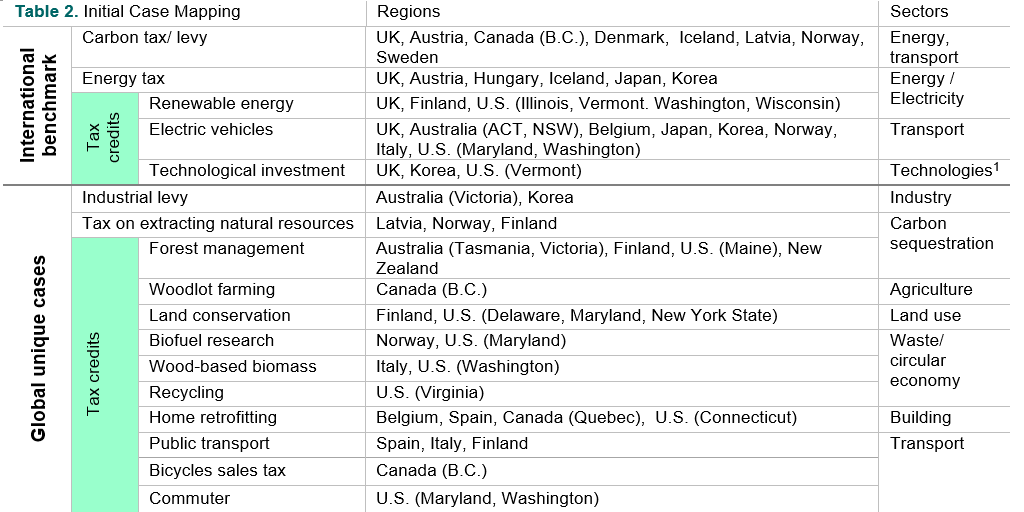

Given this typology building framework, initial case mapping is summarised in the following table:

References:

Alton, T., Arndt, C., Davies, R., Hartley, F., Makrelov, K., Thurlow, J., & Ubogu, D. 2014. Introducing carbon taxes in South Africa. Applied Energy, 116: 344–354.

Andersson, J. 2019. Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: Sweden as a Case Study. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11 (4): 1-30.

Besley, T., Ilzetzki, E., & Persson. T. 2013. Weak States and Steady States: The Dynamics of Fiscal Capacity. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5 (4): 205-35.

Carattini S, Carvalho M, & Fankhauser S. 2018. Overcoming public resistance to carbon taxes. WIREsClimChange.

Clarke, H. 2011. Some Basic Economics of Carbon Taxes. The Australian Economic Review, 44 (2): 123–36.

Craig, M. 2018. “Treasury Control” and the British Environmental State: The Political Economy of Green Development Strategy in UK Central Government. New Political Economy, 1–16.

Duit, A., Feindt, P. & Meadowcroft, J. 2016. Greening Leviathan: the rise of the environmental state? Environmental Politics, 25 (1): 1-23.

Lee, S., Pollitt, H. & Ueta, K. 2012. An Assessment of Japanese Carbon Tax Reform Using the E3MG Econometric Model. The Scientific World Journal.

Giosi, A., Testarmata, S., Brunelli, S., & Staglianò, B. 2014. The dimensions of fiscal governance as the cornerstone of public finance sustainability: A general framework. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 26(1): 94–139.

Hallett, A. H., & Hougaard Jensen, S. 2012. Fiscal governance in the euro area: institutions vs. rules. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(5): 646–664.

Mai, Q. & Francesco-Huidobro, M. 2014. Climate Change Governance in Chinese Cities. Routledge (Taylor & Francis): Abingdon, Oxon, UK. ISBN 978-1-13-878542-7

Maxim, M. 2020. Environmental fiscal reform and the possibility of triple dividend in European and non-European countries: evidence from a meta-regression analysis. Environmental Economics and Policy Studies 22, 633–656.

Mikesell, J. 2007. Changing State Fiscal Capacity and Tax Effort in an Era of Devolving Government, 1981-2003. Publius, 37 (4): 532-550.

Mol, A. & Buttel, F. (Eds.) 2002. The Environmental State under Pressure. JAI.

Mortha A., Taghizadeh-Hesary, F., & Vo X. 2021.The impact of a carbon tax implementation on non-CO2 gas emissions: the case of Japan, Australasian Journal of Environmental Management 28 (4): 355-372.

Murray, B., Pizer, W. & Reichert, C. 2017. Increasing Emissions Certainty under a Carbon Tax. Harvard Environmental Law Review Forum: 14-27.

Sommerer, T., & Lim, S. 2015. The environmental state as a model for the world? An analysis of policy repertoires in 37 countries. Environmental Politics, 25(1): 92–115.

Pereira A., Pereira, R., & Rodrigues, P. 2016. A new carbon tax in Portugal: A missed opportunity to achieve the triple dividend? Energy Policy 93: 110–118.

Yoshino N., Rasoulinezhad E., and Taghizadeh-Hesary F. 2021. Economic Impacts of Carbon Tax in a General Equilibrium Framework: Empirical Study of Japan. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management.

First published date: 25 June 2023

Updated 15 April 2025

Contact Us

If you are interested to learn more about our works, welcome to get in touch with us at

Haylofts, 5 St Thomas' St, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 4LE (by appointment),

or by email to hello@ecomuse.co.uk .

© 2026 Musecology